Spend enough time as a software engineer and you'll come to realize the best programmers are game programmers[1]. They have many cool techniques, but one of my favorites is "Structure of Arrays" (SoA).

When humans go to describe a group of "things" in code, our first instinct is to pack all of the features of said thing into a single struct, and to place those structs in an array.

pub const Human = struct {

position: Vector3,

velocity: Vector3,

health: u8,

// ... and so on

}

var humans: [64]Human;

// ...

// We would use it like

human[0].isTouching(human[1]);

human[0].isDead();

This is called "Array of Structures" (AoS), and it is slow. It's usually much faster to set it up like this, as a SoA:

pub const Humans = struct {

positions: []Vector3,

velocities: []Vector3,

healths: []u8,

// ...

pub fn isDead(self: Humans, idx: usize) bool {

return self.healths[idx] == 0;

}

pub fn isTouching(self: Humans, a_idx: usize, b_idx: usize) bool {

// ...

}

}

// And we would use it like

humans.isTouching(0, 1);

humans.isDead(0);

The interfaces for these two operations are pretty similar. One isn't more convenient than the other to write or understand. But the latter can be significantly faster than the former. Let's find out why.

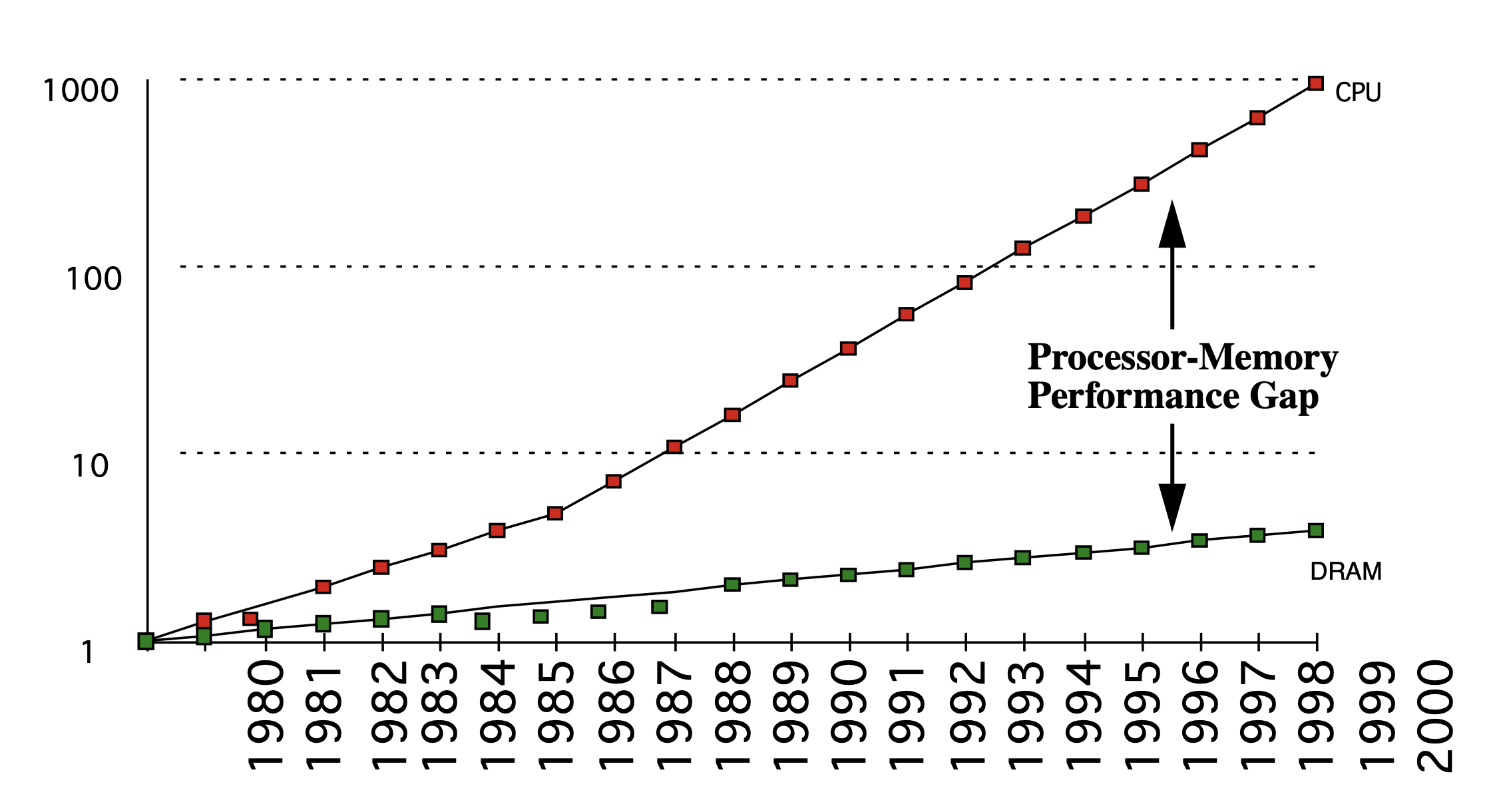

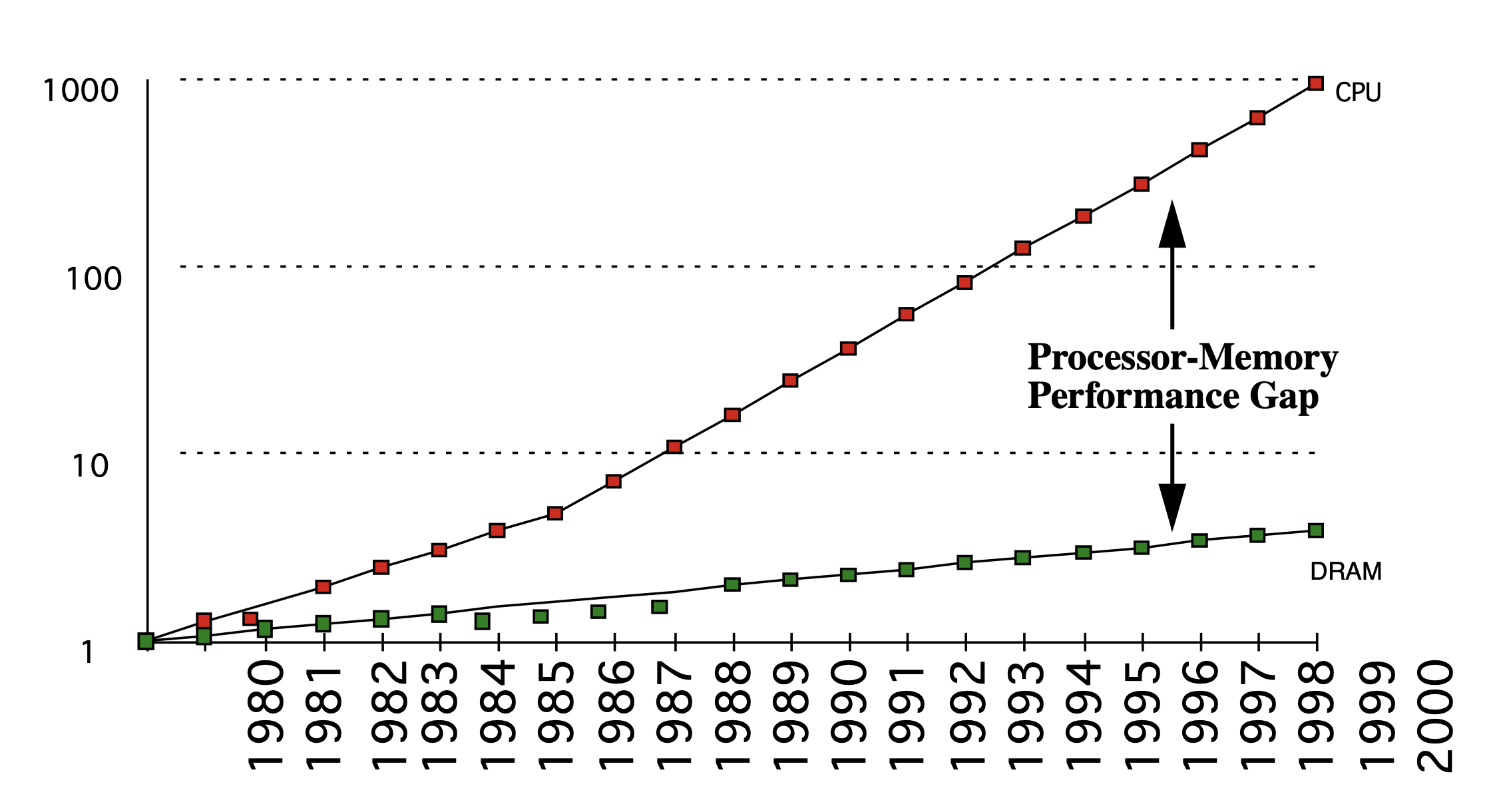

A graph of the growing gap in performance between memory and CPUs [2]

The death of Moore's law is greatly exaggerated. Since 1975, the number of transistors in processors has doubled every two years. This means that the theoretical limit to the number of calculations we can do is growing at an exponential rate. However, this is not the case for memory. Access speeds to memory have not kept up with the breakneck pace of computation speed improvement. While CPUs have improved by about 25-50% per year, memory speed improves by only about 7% per year[3]. Increasingly memory access is the bottleneck to fast computation.

To deal with this, modern processors have memory caches. Cache access speed is usually inversely correlated with size. The fastest level, L1, can only hold some number of KB of data, whereas the slowest level, L3, can hold dozens of MB of data.

While modern computers can have upwards of 128 GB of memory, only a tiny fraction of memory can be used very quickly.

I am drastically oversimplifying, but to take full advantage of these caches, you want to operate on as little memory as possible in the hot paths of your code. Allocating GBs of memory is entirely fine, but accessing a large amount of memory can make your code much slower.

I threw together a little benchmark you can find [here][4]. I simplified the code a bit for display but the general idea is still there.

Let's start with the array-of-structs implementation. The struct holds a slice of Quadratic

problems. The solve method indexes into that slice to select the problem we want to solve.

For now you can disregard the garbage field, but it will be important later on.

const AoS = struct {

data: []Quadratic,

allocator: Allocator,

const Quadratic = struct {

a: f32,

b: f32,

c: f32,

garbage: [128]u64 = undefined,

};

fn init(allocator: Allocator, count: usize) !AoS {

return .{

.data = try allocator.alloc(Quadratic, count),

.allocator = allocator,

};

}

fn solve(self: AoS, i: usize) Solution {

const problem = self.data[i];

return solveQuadratic(problem.a, problem.b, problem.c)

}

};

Compare that to the SoA implementation.

const SoA = struct {

a: []f32,

b: []f32,

c: []f32,

garbage: [][128]u64,

allocator: Allocator,

count: usize,

fn init(allocator: Allocator, count: usize) !SoA {

return .{

.a = try allocator.alloc(f32, count),

.b = try allocator.alloc(f32, count),

.c = try allocator.alloc(f32, count),

.garbage = try allocator.alloc([128]u64, count),

.allocator = allocator,

.count = count,

};

}

fn solve(self: SoA, i: usize) Solution {

return solveQuadratic(self.a[i], self.b[i], self.c[i]);

}

};

The first thing you'll notice is the interface is exactly the same. You don't have to make your

code ugly or unmaintainable to use SoA. The important difference to notice is we store each of the

fields in separate slices. When we run the solve method, we don't load the entire contents of

what was previously the Quadratic struct, we only pull in what we need. The benchmark results

are staggering:

$ hyperfine --warmup=1 './main' './main --soa'

Benchmark 1: ./main

Time (mean ± σ): 625.8 ms ± 7.2 ms [User: 266.1 ms, System: 357.2 ms]

Range (min … max): 612.8 ms … 633.8 ms 10 runs

Benchmark 2: ./main --soa

Time (mean ± σ): 22.8 ms ± 0.4 ms [User: 16.0 ms, System: 5.6 ms]

Range (min … max): 22.1 ms … 23.7 ms 86 runs

Summary

./main --soa ran

27.42 ± 0.55 times faster than ./main

The SoA code ran twenty-seven times faster! Why does this work? Because we

aren't accessing the full Quadratic struct within our hot-path. We are leaving out the huge

garbage field. In the AoS code we are thrashing our cache unnecessarily, because

we are populating the cache with lots of data we don't actually need. When we want to access the

data we actually want, it's less likely to be in the cache and we have to pull from main memory.

I am aware this is a rather contrived example. I set up this benchmark in such a way to be

maximally improved by SoA. We don't touch the garbage field at all and I iterate

over the same set of data many times. But the point still stands because even in a worst-case

scenario for SoA, the speed is about the same as its AoS counterpart. Additionally this benchmark

isn't even taking into account potential optimizations when you consider things like the

actual cache sizes and optimizing the struct alignment.

Overall, I just want to show people that performance improvement doesn't have to be ugly or even deeply technical. You can write code that is pretty AND performant. These techniques are not limited to just Zig either, they work in just about any language that cares about performance even just a little bit. If you want a deeper dive into the philosophy behind these techniques, I highly recommend Mike Acton's CppCon 2014 talk on data-oriented design[5].